Women’s chess has come a long way since Vera Menchik claimed the first Women’s World Championship nearly a century ago. The 17 women world champions have shaped the game and symbolized resilience, achievement, and progress—both on and off the chessboard.

The Queen’s Gambit series, based on a 1983 book by Walter Tevis of the same name, sparked global interest in chess. In the series, the main character, Beth Harmon, tries to make her name in the male-dominated game, facing social and personal struggles, from being shunned to being resented and discriminated. Beth Harmon’s struggles mirror the real-life obstacles top women chess players have faced—and still face today.

A look at some of the key successes and stories of the best women in chess shows how far they’ve come and how they helped shape chess to this day.

The first chess queen: Vera Menchik

Vera Menchik was the first woman to break the barriers of male-domination in chess, sowing the seeds for other great women players who followed.

When Vera Menchik sat down at the chessboard in 1927, little did she know she was about to leave a big mark on history, starting a tradition that has lasted until today. As the first Women’s World Chess Champion, she wasn’t just moving pieces on a board—she was making a statement in a world that barely acknowledged women could play the game at all.

In the summer of 1927, FIDE organized the first Olympiad or, as it was called then – the Tournament of Nations. In addition to the Olympiad, a women’s tournament was organized which was won by the 21-year-old Vera Menchik (with 10.5/11, drawing with Edith Michell) which led to her being declared the first Women’s World Chess Champion. She would go on to become the dominant figure in women’s chess – the longest-reigning women’s world champion, with eight titles – until her life was tragically cut short in the German bombardment of London in 1944. She died as Vera Stevenson (she was married to Rufus Henry Streatfeild Stevenson (1878–1943), a prominent figure in British chess, serving as the Honorary Secretary of the British Chess Federation (BCF).

Menchik’s era happened between two world wars, when – similar to today – much of the planet was on the edge and the cause for women’s rights (and the rights of other marginalized groups) was on the fringes of society. During this time, when FIDE was still taking shape, women did not enjoy many privileges or support in chess, but Menchik proved her worth standing shoulder to shoulder with the top male players in tournaments – defeating the likes of Yates, Euwe, Sultan Khan, Reshevsky, and Mieses.

Post WW2: The Soviet women dominate

Post-war, the Soviet Union became the epicenter of chess. Instead of matches which were practiced in the open (male) events, the Women’s World Champion was determined through tournaments.

Lyudmila Rudenko (who was one of top swimmers in Ukraine before turning to chess!), claimed the title in the first post-war tournament, in Moscow in 1950. She lost the crown three years later to Elisaveta Bykova, who taught us all about second chances: Despite losing to Olga Rubtsova in 1956, Bykova reclaimed her title in 1958 and again in 1959, holding it until 1962.

But it was Nona Gaprindashvili who really shook things up and took women’s chess to the next level. First, she claimed the title in epic style, defeating Bykova (+0 -7 =4) in 1962, at the age of just 21! This led to the launch of a chess revolution in her native Georgia which, to this day, is one of the strongest chess nations in the world, particularly in women’s chess.

Gaprindashvili didn’t just dominate women’s chess—she challenged men directly, competing successfully in male-dominated events. Thanks to this, in 1978 she became the first woman in history to be awarded the title of Grandmaster.

Despite losing her world crown to compatriot Maia Chiburdanidze in 1978, Gaprindashvili continued competing at the top for another two decades. Her successes also include playing at 12 chess Olympiads (11 times for the USSR and one time for her native Georgia, in 1992, in their first international appearance since gaining independence). A national hero of Georgia and a living legend of chess, Gaprindashvili (now 83) still takes part in chess events (for seniors) and in 2024 toured several countries in the world to talk about the sport.

Then, a new world champion and a new chess milestone for women: another Georgian, Maia Chiburdanidze, became World Champion in 1978, at the age of just 17 – an unprecedented success in women’s chess, matched only by Hou Yifan decades later, and still unmatched among men. After four successful defences of the world crown, her reign ended in 1991 when Chiburdanidze lost the title match to Xie Jun of China (+2-4=9).

The first Chinese chess moment

The chess world’s center of gravity shifted eastward in the 1990s when Xie Jun clinched the crown – becoming the first ever women’s chess champion from Asia. This victory wasn’t just personal—it signalled a new chess superpower was emerging in the east.

Xie’s meteoric rise in chess stands as an example of her country’s rapid global advancement by making giant leaps in short periods. Xie Jun took up chess as a child and by age 10, she was already the champion of Beijing. By the age of 14, she was the girls’ champion of China. In 1991, at the age of 21 – Xie defeated Maia Chiburdanidze to become the first Chinese World Chess Champion.

Then in 1993, the 23-year-old Xie achieved another milestone – the first among nearly 1.7 billion women in Asia to claim the title of Grandmaster. That year Xie successfully defended her world crown against Nana Ioseliani (winning the match 8.5–2.5). Her reign would continue for another three years – until Susan Polgar came to the fore.

The Polgar sisters

It is not uncommon in sports to have sibling or family members make huge successes. But, hardly any sport can match the trio of three sisters from Hungary – Judit, Susan and Sofia Polgar – who gave new vigor to women’s chess. While previous champions had risen through traditional chess structures, the Polgar sisters’ ascent was different: Their father, Laszlo Polgar, was determined to prove that “genius is made, not born”.

All three achieved remarkable feats: Susan became the first woman to earn the men’s Grandmaster title through regular tournament play, Sofia achieved the highest single-tournament performance rating in chess history for a woman, and Judit (who became a GM at the age of 15, breaking Bobby Fischer’s record) rose to become the strongest female player ever – defeating 11 world champions and ranking among the world’s top 10. With a peak rating of 2735 in July 2005 (on par with top male players of the time), Judit is still the highest-rated female player in history.

While Judit decided not to compete in women-only events, her sister Susan went all the way and claimed the women’s title in 1996.

The success of the Polgar sisters challenged long-held beliefs about gender and intellectual capability. Their story proved that with proper education and opportunity, women could compete at the highest levels in traditionally male-dominated fields.

The Chinese era in women’s chess

Three years after losing her title to Susan Polgar in a dramatic match in 1996, Xie Jun was again back at the top. She regained the title in 1999 by defeating another championship finalist, Alisa Galliamova (8.5–6.5), after Polgar refused to accept match conditions and forfeited her title.

Xie was then succeeded by compatriot Zhu Chen, who held the crown till 2004.

Zhu Chen not only won the world title but also became the first champion to forgo defending it due to pregnancy—highlighting the challenges of balancing chess with motherhood. She also pursued higher education, studying literature at Tsinghua University.

China’s dominance was briefly interrupted when Bulgaria’s Antoaneta Stefanova held the title from 2004 to 2006. Then Xu Yuhua regained the crown for China in 2006.

Sometimes success comes when you least expect it. Xu Yuhua entered the 2006 Women’s World Championship while three months pregnant and stunned the field, winning the title by defeating Alisa Galliamova. She lost the crown in 2008 after a second-round exit, passing the title to Alexandra Kosteniuk.

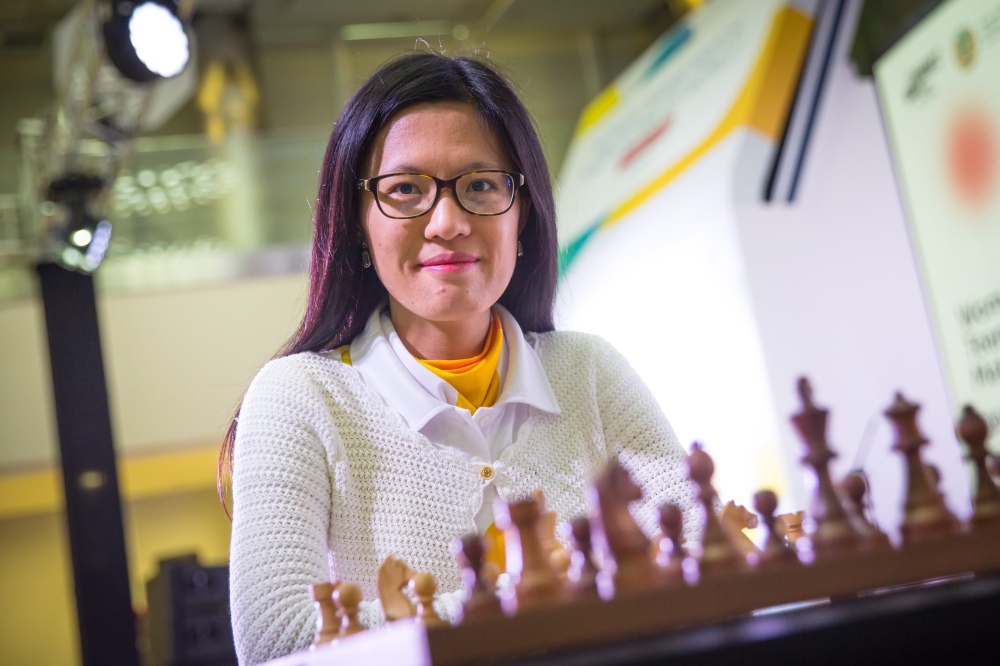

In 2010, another Chinese player, Hou Yifan, won the crown at just 16, becoming the youngest Women’s World Champion in history. She went on to claim the title three more times (2011, 2013, 2016) and, even today, remains the world’s top-ranked woman player—despite stepping away from serious competition. Unlike many former world champions, for whom chess remains a lifelong pursuit, Hou charted a different course. She turned her focus to academia, studying international relations in China and at Oxford. In 2020, at just 26, she became the youngest professor at Shenzhen University, later joining Peking University, where she continues her academic career.

During Hou’s time, the dominance of China was briefly interrupted twice: by Anna Ushenina in 2012-2013 and Mariya Muzychuk, in 2015-2016, both from Ukraine.

In 2017, another Chinese woman came to the fore: Tan Zhongyi. A chess prodigy with a consistent record of high performance, Tan won her title in Iran in a knockout event featuring 64 of the strongest women players. She would, however, lose her crown the following year to Ju Wenjun.

Despite her short-lived reign, Tan continued to play strongly and remain among the world’s top women players. As the winner of the 2024 World Candidates, Tan will once again fight for the world chess crown against Ju Wenjun, setting the scene for a great comeback.

The reigning champion Ju Wenjun’s path was distinctive from the start—inspired by Xie Jun, she eschewed junior competitions in favor of playing against adults from a young age. After finishing second in the Asian Championship at just thirteen, she maintained a steady upward trajectory, qualifying for her first World Championship in 2006. Ju’s breakthrough came with her 2015-2016 FIDE Women’s Grand Prix victory, which earned her a title match against Tan Zhongyi.

Since dethroning Tan in 2018, Ju has compiled a remarkable championship record, becoming the first woman since Xie Jun to successfully defend her title in a knockout format (Khanty-Mansiysk, 2018), surviving a tiebreak against Aleksandra Goryachkina in 2020, and securing her fourth title with a dramatic final-game victory against Lei Tingjie in 2023.

The future of women’s chess

In recent years there have been significant efforts, primarily by FIDE, to promote women’s chess, including the introduction of the Women’s Grand Prix series, which now consists of six tournaments.

The match between Tan and Ju in April 2025 is another important milestone, not just for chess but also for China, which is hosting the match for the sixth time. Fifty years since China joined FIDE (1975), the country is one of the strongest chess nations in the world: it had a world champion in both the open and the women’s competition, it is the first in the number of women world champions (six, followed by five from the USSR), and, most importantly, it has a number of players in the top-100. But with such success comes great responsibility – to support and spread chess.

Still, many challenges remain for women’s chess – from more sponsorship to public recognition. But one thing is certain—women like Menchik, Gaprindashvili, Hou, and Polgar haven’t just played the game; they’ve transformed it.

Next time you set up a chessboard, remember: the queen is the most powerful piece for a reason. The women of chess haven’t just played the game—they’ve redefined it, breaking barriers and reshaping history one move at a time.

Written by Milan Dinic