In memory of Vasily Smyslov

Photo: Koen Suyk / Anefo 2021 is a year of remarkable anniversaries. Vasily Smyslov was born on 24 March 1921, precisely 100 years ago. The winner of the famous Zurich 1953 Candidates Tournament, Smyslov played his first match against Mikhail Botvinnik in 1954. It ended in a draw, with seven wins from each side, so the champion retained the title. In the next cycle, Smyslov won the Candidates Tournament (Amsterdam 1956) again, this time to beat the patriarch 12½–9½ in 1957 and become the 7th World Champion. Photo: Boris Dolmatovsky Botvinnik took the title back in a rematch next year, but a short reign did not extinguish Smyslov’s passion for the game. Just like Korchnoi, Smyslov boasted exceptional longevity in competitive chess. To mark the date, the Chess Federation of Russia published an article in which GM Dmitry Kriakvin reflects on longevity and centenarians’ topic. We publish an excerpt dedicated to Smyslov. He was a member of the world chess elite until the 80s and accomplished the impossible – a record that will never be broken. In 1984, at almost 63 years old, Smyslov reached the Candidates Matches’ final to be stopped only by Garry Kasparov, who was soaring to the top. Right before that, Vasily Vasilievich finished second in the Interzonal (Las Palmas 1982), ahead of Jan Timman, Tigran Petrosian, Bent Larsen, Vladimir Tukmakov, Lev Psakhis, and other grandees. In a dramatic quarterfinal against Robert Huebner, he made it to the next round only by drawing lots. When all tiebreak games ended in draws, the qualification spot was decided in a casino. The German grandmaster did not have the nerve to attend the procedure. Smyslov, however, calmly took his place at the playing table and did not even blink when the ball halted on zero at the first attempt. The second spin favored the former world champion. Photo credits: D. Fligelis via chesspro.ru In the semifinals, Vasily Smyslov defeated Hungarian Zoltán Ribli, and although his dream to face Anatoly Karpov did not come true, he remained the most dangerous opponent for players of any level for a long time. For example, in a 1988 USSR Championship with a phenomenal lineup, Vasily Vasilievich finished in the middle of the final standings – he beat Viacheslav Eingorn, Vassily Ivanchuk, and Jaan Ehlvest. In Tilburg (1992), held in experimental at that time knockout format, he went through three rounds, eliminating much younger Boris Gulko and Grigory Serper. In the round of 16, Smyslov scored first against Evgeny Sveshnikov, but his opponent managed to bounce back and then snatched the victory in the match. Your author saw Vasily Smyslov for the first time at the Igor Bondarevsky Memorial in Rostov-on-Don in 1993. The battle for the first place in the main event unfolded between Sergey Tiviakov, Lev Psakhis and Vladimir Epishin, with the latter two finishing half a point behind in the end. Smyslov performed not too well but saved a fantastic endgame against Psakhis, which I did not manage to spectate till the end – it went dark, the hall got empty, and my parents took the young chess fan home. Nowadays, both computer and Lev Psakhis confirm that the veteran defended just amazingly. Photo: Alexander Yakovlev/TASS Vasily Smyslov was active for a very long time. His favourite competition was, without doubt, a then-popular match “Ladies against seniors”. He visited distant and hot India, competed in the Highest League of the Russian Championship and knockout world championships, was a sparring partner for young stars, and scored solid 2 out of 6 in the 1997 match-tournament facing Emil Sutovsky, Judit Polgár, and Loek van Wely. In his last match with the ladies (2001), at 80 years old, he netted 5 out of 10. Later he could not compete anymore because of the eyesight problems – doctors prohibited him from playing. The legendary chess player passed away on March 27, 2010, a few days after his 89th birthday.

Arbiter’s Commission programme for online and hybrid events

“Dear Member Federations, The FIDE Arbiters’ Commission is proud to release a new programme to support the development of arbiters in online and hybrid events. Two levels of seminars have been designed: A Basic Course (8 hours) to cover roles and duties of Online Arbiters and Local Chief Arbiters in hybrid events. An Advanced Course (8 hours) to cover the roles and duties of Chief Arbiters for online and hybrid events. Official FIDE events will soon require arbiters worldwide to supervise players in hybrid events. The Arbiter’s Commission has proposed that FIDE covers the training of at least 1 or 2 arbiters per federation on the Basic Course and we are very happy that we got strong support from our colleagues from the FIDE Planning and Development Commission and the FIDE Management. With this letter, we are inviting you to select 2 arbiters from your federation to take part in the Basic Course. This way, our objective is to train about 400 arbiters worldwide. The training fees of this first wave of training will be covered by the FIDE Development Fund, which means no cost for federations or selected arbiters. If your federation wishes to send more candidates, additional arbiters are welcome and may be included in the training at the standard cost of 30 €. Please note that in terms of planning we may consider initial trainees from federations as having the priority over the extra trainees so that we cover as many federations as possible in the short term. Please send to the FIDE Arbiters’ Commission (secretary.arbiters@fide.com and chairman.arbiters@fide.com) the names and email addresses of your selected arbiters so that we may plan their registration to the appropriate sessions. Please consider for selection, arbiters of the following profile: FIDE Licensed Arbiters (preferably IA or FA) Level of English strong enough to follow the sessions IT skills strong enough to connect to the sessions and understand/apply online concepts Arbiters likely to be involved for your federation in the local supervision of FIDE hybrid events You will also find attached a 1-page description of the courses for a better understanding of the content. Sessions will usually be 4 times 2 hours of online courses. As we intend to start the first sessions at the beginning of April, please get back to us as soon as you can and before the 4th of April 2021. Looking forward to a fruitful collaboration on this project, we wish you good health in this difficult period and successful online/hybrid chess events. FIDEOnline/HybridArbiter Training (PDF) Laurent Freyd, FIDE Arbiters’ Commission Chairman”

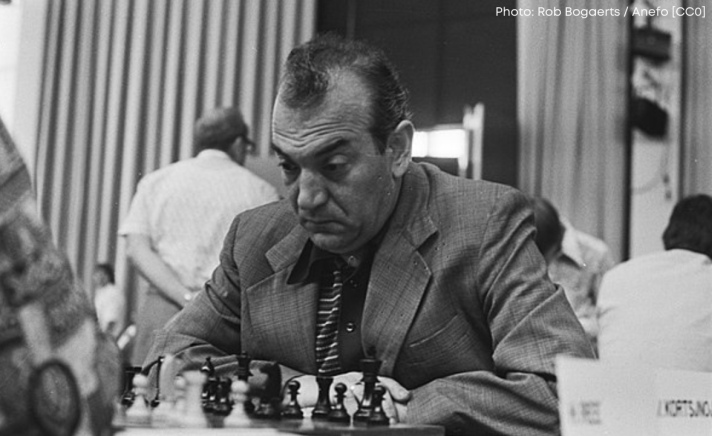

Emil Sutovsky on Viktor Korchnoi

Viktor Lvovich Korchnoi would have turned 90 yesterday. He is one of those monumental figures one returns to time and again when writing about chess. What would most people know about Korchnoi nowadays? A strong player, an incredible fighter, a cranky guy. These traits can’t be argued, and they are well-known; I would like to give nuances and details on a character that were more hidden from the world. First and foremost, Korchnoi’s attitude towards chess. It was strikingly different from the approach of the majority of his colleagues, even the greatest ones. Arguably, Korchnoi became the first one to make “Fighting to the last bullet” his chess motto. He kept this aggression burning throughout his long career and probably was the best chess player in history when it comes to fighting spirit and resilience. Korchnoi was one of the few (perhaps along with Geller, Polugaevsky, and Fischer) who toiled over chess incessantly. It helped him to permanently stay in shape. Quite funny was to hear the young players lament exhaustion after working with the seventy-year-old Korchnoi at a training camp. Viktor Lvovich (simply Viktor back then) grabbed material in a way that was later to be labelled “computer-like,” but still was ready to fend off his opponent’s attacks (please note, that despite his pawn-grabbing propensity, Korchnoi rarely came under a crushing attack). The word “dangerous” was not in his vocabulary. He neither guessed nor made rough estimations; he just diligently calculated numerous variations. This, incidentally, explains his overwhelming record against Tal. Photo source: http://gahetn.nl It was Korchnoi who, 40-50 years ago, long before Carlsen was born, became a great (probably the best in the world) master of a complex endgame. He was particularly strong in rook endings. Striving for a real fight and for opportunities to overtake the initiative over the chessboard throughout his career, Korchnoi frequently used difficult openings (French Defence, Pirc Defence). But he also had a great opening intuition – in a letter, written in 1972 (published in the excellent book “Russians vs. Fischer”), Viktor Lvovich advised Spassky when in preparation for his match with Fischer: “From the play-to-equalize standpoint, I suggest paying attention to the Petroff Defence and 3…Nf6 in the Ruy Lopez”. Nowadays these continuations (along with the Marshall counterattack and the Sveshnikov Variation of the Sicilian Defence) are Black’s most solid response to 1.e4 – but back then both the Petroff Defence and the Berlin Variation of Ruy Lopez were in the fringes of opening theory! In fact, Korchnoi was the first and only one for decades to use the Open Variation of the Ruy Lopez – currently, the majority of the best players have this line in their opening repertoire. Korchnoi was never an easy man, and, drawing parallels to the present day, was a great master of trash-talking, so popular among the leading young chess players nowadays. On the other hand, “Viktor the Terrible” won over chess fans with his unfailing love of chess, ever-burning fighting spirit, and desire to give it all on the battlefield. Elegantly dressed, distinguished-looking, and always eloquent, but he could be different each time you met him – from prickly and caustic to charming or infectiously laughing. Korchnoi was invariably gallant in female society but often irritable and scathing with his colleagues. Ready to talk endlessly about chess and chess-related topics, he had tenacious memory. Viktor often quoted the classics of literature (Pushkin for example) and chess players of the past (“but Levenfisch said…”). At times Korchnoi was unexpectedly respectful and open with young colleagues outside the tournament hall, but one could see him nervous and at times aggressive during and immediately after a game. From Korchnoi’s personal archive, via ruchess.ru Usually, Viktor showed mercy to his defeated opponents, but once he remarked immediately after the game we played, in which I intuitively sacrificed a piece in a position with a huge advantage, but was unfortunately left high and dry: “Do you think you’re Tal? Even Tal didn’t sacrifice me a piece without calculating variations. And you are not Tal.” He was admired by many, but it was hard to imagine a person who could tolerate the irascible Viktor Lvovich. Frau Petra managed it, although not without difficulty – perhaps because their life together was based on mutual respect. Today you cannot imagine married couples who address each other exclusively as “You”. Another reason might be that she went through a school of hard knocks and became just as tough a fighter herself. Korchnoi as a chess player was treated with fearful respect, but an even greater number of people found his behaviour during/after a game unacceptable, and yet, the Greats are forgiven more sins than mere mortals. He was forgiven not only for his magnificent play but also for his dedication to chess, for that genuine commitment over the board. Karpov once said: “Chess is my life. But my life is not just chess”. Korchnoi could have easily discarded the second half of that quote. Viktor Lvovich pushed every conceivable boundary, surpassing even Lasker. At 70 he won a super-tournament in Biel finishing ahead Gelfand, Grischuk, Svidler, and others, and at 80 he put in a good performance in Gibraltar, defeating, among others, Caruana, who had already begun his meteoric rise… And yet Korchoi’s best period is the 1970s. His epic duels with Karpov are still talked about. But there were so many other remarkable battles: the matches with Spassky, Petrosian, Polugaevsky… Even in the match against Kasparov (1983), for the most part, he was fighting on equal ground. We often talk about the most interesting unplayed matches – one of the most interesting for me would have been the Candidates final between Korchnoi and Fischer (1971). But Korchnoi lost to Petrosian in a very strange semi-final. The duel with the American genius did not take place. It is a pity because Viktor Lvovich was effective against Fischer; he controlled the proceedings in their last game back in 1970. Korchnoi remains a controversial figure.