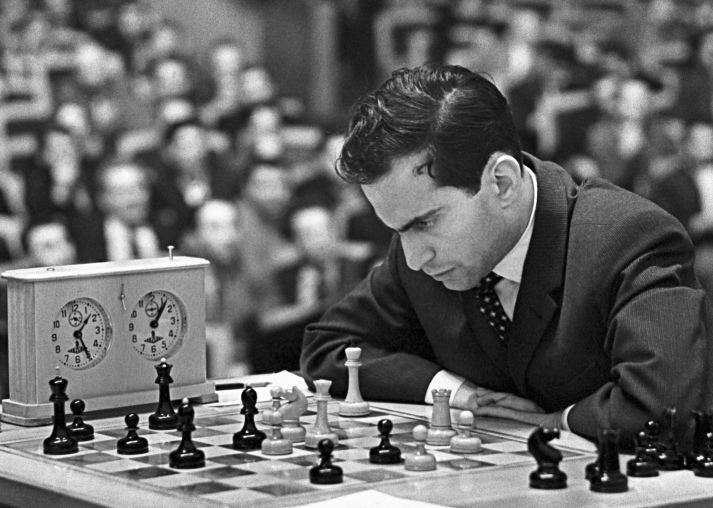

Emil Sutovsky on Mikhail Tal

November 9 was the birthday of Mikhail Nekhemevich Tal. Magical, unearthly, amazing. His family name, which means “dew” in Hebrew in many ways reveals the essence of the fresh, fragile, and short-lived genius from Riga. He was like a dewy bead – appearing out of nowhere in that symbolic 1956, Tal became a whiff of fresh air in his first USSR Championship. Four years of incredible success followed. He played different chess seemingly flouting all the existing rules. A very young Misha, with an incredible energy and almost mystical appearance, soared to the very top. He was cocky, devilishly dodgy, and divinely beautiful while battling with the best players of the older generation, and even Botvinnik himself had to lay down his arms. Tal became the world champion. He was admired by the audience and the gentle sex – open, wanton, very young, “du soleil plein la tête”. But then began a long black streak. Misha – as he was called until the last years of his life, despite any age gap – had serious health problems. This affected his preparation for the rematch against Botvinnik, and Tal was crushed by his 50-year-old namesake. Nevertheless, Tal cheerfully remarked that he was now the youngest ex-world-champion ever. Oh, his amazing sense of humor. No world champion delivered so many memorable phrases, remarks, comments, and puns as Tal did, and that sums up Tal for me. His cheery disposition must have helped him survive his numerous health problems. He could have just sunk into a depression and never returned to the game. He cast his magic, played chess, and lived for it – tournaments, simuls, publications, endless blitz games. How about working on his chess or attending some training camps? Nope – at some point, Misha’s long-term mentor and coach Alexander Koblenz just stopped trying to change anything. Photo: Harry Pot But there was no room left for daily routine and domestic life. Tal was absolutely indifferent to these matters and simply sidelined them. Organizational and monetary issues only distracted him. The young Tal could walk around in two different shoes for several days, be regularly late for flights; later in his life Misha could forget about a prize of many thousands or just lose a large sum of money. As for all these Soviet realities – they just hindered him. Just like that pawn from a dialogue with Botvinnik during one of the Olympiads: “Misha, why did you give up a pawn? – It disturbed me.” Tal was in no way anti-Soviet, he did not even notice the system’s shortcomings – all he needed was not to be distracted from his calling. But he was distracted a lot and first of all by his numerous diseases. In 1962, he took part in the Candidates Tournament, hoping to qualify for the championship match again. Dream on! Having spent three-quarters of the tournament on pills, Tal ended up in a hospital. A sick kidney – that’s where young Misha’s troubles began, and thirty years later there would not be a single normally functioning organ in his body. Always with a cigarette – he chain-smoked two packs a day, not a stranger to alcohol, and absolutely disinclined to practice any sport, he burned himself out, but it is simply impossible to imagine him otherwise. Back in the 1960s his young body recovered, and in 1964 the magician from Riga was back on track – he tied for first in the Interzonal (scoring +11 without a single loss), then consecutively beat Portis and Larsen only to lose in the final Candidates match to Spassky, formally becoming the third-ranked player on the planet. The Olympiad in Havana (1966) nearly ended tragically for Tal. A bottle hit his head in a bar – either thrown by mistake or out of jealousy – and sent Tal back to a hospital cot. As Petrosian ironically put it “only Tal with his cast-iron health could come round so quickly” – in a few days Tal was back steamrolling his opponents. Here I would like to elaborate a little bit. Tal was incredibly good against players, albeit strong, but inferior to him. Using psychology brilliantly he would get his opponents to question themselves, fall into time trouble, and make mistakes. However, facing players of his own caliber – world champions, as well as good counterpunchers like Korchnoi, Polugayevsky, Stein – he had a hard time. His creativity lifted him high but harsh reality often brought him back, a few pawns, and sometimes pieces down. When Tal was in normal physical condition, such a style worked even against the best of the best – healthy Tal, healthy spirit, healthy game – but when he wasn’t optimal, it ended not with a bang but with a whimper. During the late sixties, his health failed him more and more often. Major newspapers even prepared obituaries, although Misha was only about thirty. In 1968, he crashed out of the next cycle world championship cycle, losing the match to Kortchnoi. A prolonged crisis ensued: Tal did not make it to the Olympic team, and in Lugano (1968)he was replaced just a day before the departure as if being ostentatiously discarded. The authorities preferred older Smyslov, who did not have a good ground to be a part of the team but was on good terms with Soviet officials. By the way, it also makes Tal very special. Botvinnik, Petrosyan, Smyslov, Karpov – all of them, although to a different extent, were authorities’ darlings. Tal was not. Neither was Spassky. But Spassky was a rebel and did not want to keep his mouth shut. As for Tal, he was alien to all these considerations. Photo: Ron Kroon / Anefo The late sixties and early seventies was not a joyous time for Tal. He tried to change his game style, knowing that his signature squares f5 and d5 were now securely covered, but these attempts did not yield results. He wasn’t even allowed to play in the USSR Championship in 1970, which was held in his native Riga. He

SCC Round of 16: So beats Abdusattorov

In the fourth match of the 2020 Speed Chess Championship Main Event, GM Wesley So (@GMWSO) defeated GM Nodirbek Abdusattorov (@ChessWarrior7197) 18-10. Except for a brief comeback from Abdusattorov at the end of the five-minute portion, So dominated the match from start to finish. He brought his great play at the American championship into his next tournament while the Uzbek youngster couldn’t find his best form. So played the match from his home in Minnetonka, Minnesota; Abdusattorov played from Tashkent, Uzbekistan. The players in this competition play with two cameras (for fair play reasons). Since both of them had no problem with Chess.com showing the cameras in the broadcast, the fans had the opportunity to see their setup: So, who played with a relatively small board in the corner of a big computer screen, started with three wins—all three scored in endgames. His opponent was fairly close to a draw in game two but couldn’t hold it in the end. After a draw, So won a quick game in a Two Knights Defense that gave him a four-point lead. Abdusattorov referred to this game afterward: “His opening preparation was amazing. [In this game] he just crushed me.” In game six, Abdusattorov finally got his first win. “I said to myself, OK, I need to play faster and my best. And then it became very close,” he said afterward. The next game ended in a draw, but then the Uzbek GM won two more. Suddenly he was just one point behind. So later admitted that this was the first of two times in the match that he “tilted.” The five-minute portion ended with one more draw, which meant the score was 5.5-4.5 with So leading. The American player started the three-minute segment with a win but then blundered again. Those who hoped to see a close battle at this point got disappointed as So won five games in a row to take a commanding six-point lead. That blow Abdusattorov couldn’t recover from. Wesley could even have entered the bullet portion with a slightly bigger lead as he missed a win in a pawn ending in game 19. By winning the first three bullet games, So made it clear that he wasn’t going to allow another comeback. The second moment Wesley went on “tilt” was at the very end. Leading 18-8, he lost the last two bullet games that gave Abdusattorov both a more decent-looking final score and some extra prize money. So said he got “a bit careless” halfway in the five-minute segment: “Actually, I was quite angry with myself because first of all, I lost on time in two or three games. That’s frustrating. After the first four wins, I thought the match would be comfortable, but then Nodirbek played very well today. He is always looking for a fight. He gets fighting positions with both white and black, so it’s hard for me to consolidate.” Abdusattorov won $714.29 based on win percentage; So won $2,000 for the victory plus $1,285.71 on percentage, totaling $3,285.71. He moves on to the quarterfinals, where he will play the winner of GMs Fabiano Caruana and Jan-Krzysztof Duda. The 2020 Speed Chess Championship Main Event is a knockout tournament among 16 of the best grandmasters in the world who will play for a $100,000 prize fund, double the amount of last year. The tournament will run November 1-December 13, 2020 on Chess.com. Each individual match will feature 90 minutes of 5+1 blitz, 60 minutes of 3+1 blitz, and 30 minutes of 1+1 bullet chess. Text: Peter Doggers Photo: chess.com